To Save Water, Pay for it

As California struggles with its worst drought in its history, I'm stunned at how little it seems to matter in terms of people changing their habits and plans. For a state so populous, and so reliant on such limited supplies of ground and river water to quench the thirst of its farmers, residents and businesses, sweet little was done till recently to implement conservation measures. Housing continues to sprawl, farmlands continue to be paved, and even more cars get even bigger. I don't mean to pick on California though. Over 90% of Texas is currently a dust bowl of denial with a far bigger problem than California has on its hands, and its God-fearing, finger-pointing, creationist politicians have their climate-change denying heads buried in their oil wells.

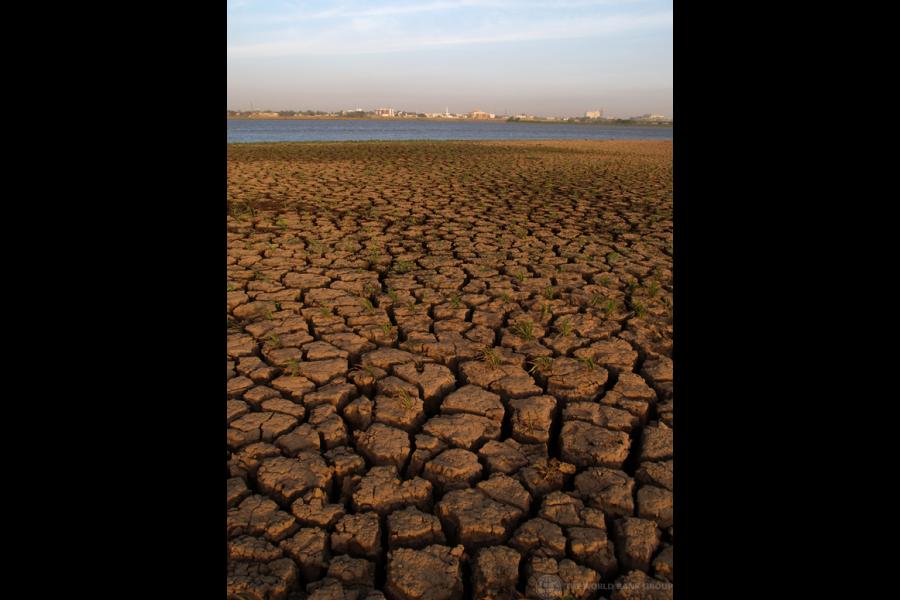

I'm saving the climate change angle for a future piece though. This post is about how absurdly indifferent and apathetic people can be, and how we might try to change that. Water is our most precious, life-giving resource. Though it covers 70% of the surface of this planet, barely 1% of it is potable. Yet, we don't realize how scarce and valuable it is till we lose it.

Instead of working with natural ecosystems and planning for growth in sustainable ways, governments foolishly try to master it, and I would argue that they do so with little success and at a very high cost. So enamoured are nations with grand solutions, that countries like India and China have developed grandiose plans to build canals linking rivers across vast geographies. Instead of taming and shaping population growth, and matching development with the carrying capacity of the land and water they rely on, to ensure sustainability and have the least impact possible, we've tried to engineer band aids at great costs. No amount of litigation, wealth, prayer, or political effort is going to make it rain. We have to stop pretending that we don't have a problem.

I'm not a fan of blind privatization as being the answer to our problems, but I do think that we need to start paying, even if it is to ourselves, the true cost of what we use. Financial incentives and disincentives play a key role in shaping our behaviours. Making people pay for plastic bags can lead to an over 90% decline in their use. Why can't we apply the same approach to water?

The map below, with data from Global Water Intelligence, shows what a cubic meter of water is worth all over the world.

I dug a bit deeper. Keeping per-capita GDP levels as a baseline, my analysis showed that someone in Mumbai, pays the same share of his or her income for a cubic metre of water, as someone in LA. However a resident of the Amsterdam pays almost 2.5 times more than what someone in LA or Mumbai might pay. In short, the ratios are all over the place and hide what is really happening on the ground.

What we do know through some excellent research done my my friend Dr. Renu Desai (Water Wars in Mumbai) and her colleagues, is that water does have a price. Their data and analyses are compiled by Durham University in a very informative website: Everyday Sanitation: A comparative study of Mumbai's informal settlements. Based on her research, some of it included in the Water Wars section on the website, approximately half of Mumbai's population does not have access to potable water. These marginalized residents, usually in slums "paid between Rs.5 to Rs.20 for a 35-litre [or up to $252 per cubic metre] can of water - between 30 and 200 times more than the official municipal water tariff for slums. Given that the so-called 'water mafia' involves loose collections of middlemen, municipal officials, politicians and the police, there is often a vested interest in raids in removing legal connections as well as illegal ones."

Scarcity of any kind makes for a black market in that good or service. Let's use this same pricing pressure then to temper demand. While a cubic metre of water may legally cost $0.22 in Mumbai, there's little of it to go around, but plenty at $252. The same question could be asked of LA. How much more water will you sell at $2.82 till you run out of it?

Try telling a Texan to sell the last drops of his oil at a fraction of its market value, and he'll draw one of his many guns on you. Why don't we think of water the same way? If a slum-dweller in Mumbai can pay $252 per cubic metre of water, then surely Mumbai and LA could charge a little bit more. People would use less, and get a better, more reliable, financially AND environmentally sustainable water supply in return. Perhaps we could aspire to charge a little bit more than that to replenish the basins we've drained and safeguard supplies for future generations? This boy can always hope.

California did finally act. According to an article in the New York Times titled In California, Spigots Start Draining Pockets, hikes in water rates coupled with rationing by some of California's municipalities, have changed how residents are using a resource they had till yesterday taken for granted (albeit with a lot of complaining and whining). It warmed my heart to also come across an article in Punch, where a bartender argues for more sustainable, water-conserving approaches to brew liquor, in his effort to save his planet. Cheers to him. After all, every drop counts...